So, what’s the best espresso machine?

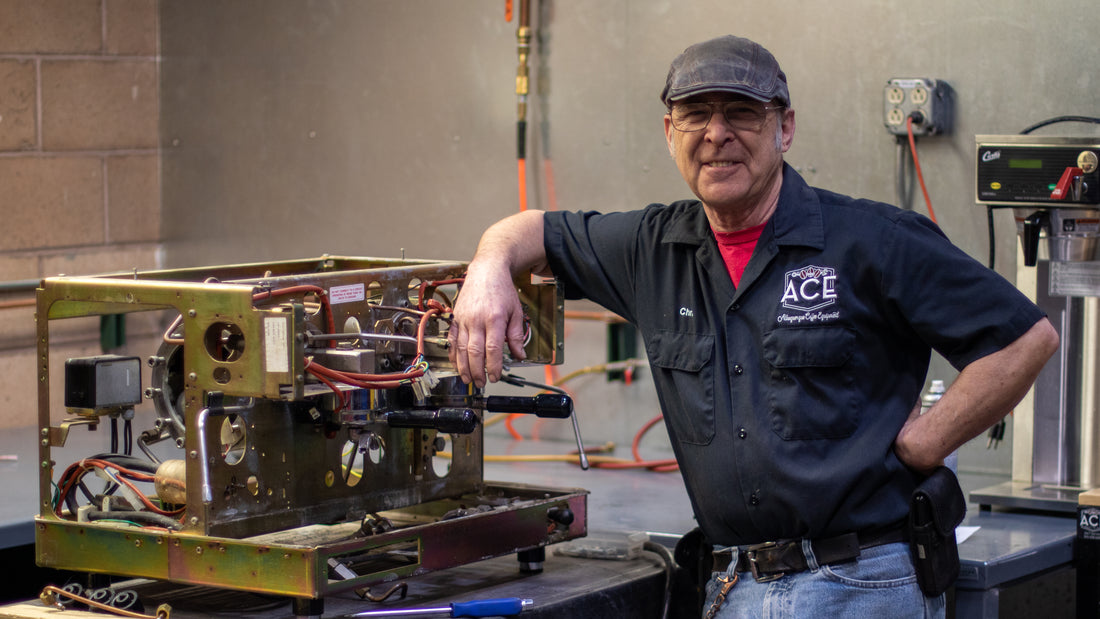

Hi, my name’s Chris Stripling. To preface this, I now have two jobs. Five and a half years ago, I left ACM here in Albuquerque when ownership changed hands and where I’d worked for twenty years, give or take. From there, I came onboard at New Mexico Pinon Coffee Company as an equipment tech. Now I’m their Facility Engineer where my team cares for the production equipment. Three years ago, Mike Paduano (another former ACM employee) and I helped launch Albuquerque Coffee Equipment where I’m the Lead Technician and continue to keep my hands inside of espresso machines.

I’ve often been asked, “What’s the best espresso machine?” Early on in my espresso career, I would’ve immediately answered “An Astoria.” But that’s because those were the best espresso machines for me.

I’ve been working on coffee brewing equipment for longer than I care to remember. I started working on Bunn RL’s and OL’s (the old ‘50’s looking machines in Denny’s Restaurants.) We had them in the 7-Eleven’s here when I worked as a maintenance engineer for Southland Corp in the late ‘80’s. That experience later got me a job at ACM here in Albuquerque in the mid ‘90’s. It was there I got to work on espresso machines for the first time. Many of the first ones were owned by Aroma Coffee in Santa Fe NM. Some were Astorias. There was a smattering of other brands: Brasilia, Rancilio, Bunn (made by Gaggia and Futurmat), San Marco, Marzocco and other names I’ve lost over the years. That brought me up to Santa Fe on service calls where I ran into a smorgasbord of different brands from Ascasio to Wega.

I learned espresso machines are like cars.

So, which is better, Chevy or Ford? Or Dodge? Toyota? Tesla? Citroen? Daewoo? Lots of choices. Lots of price points. Lots of different features.

I started out as an auto mechanic. Wired cars and built engines for 10 years. I was 5’6” and 135lbs back then, not physically built for heavy line work. I liked engines, did well at them, but heavy line work was hard on me. I liked wiring, too, though back then it didn’t pay much. But I saw the insides of a lot of cars and formed opinions about them that surprisingly hold true today.

I’ll start out by making the “bowtie” guys mad at me. GM’s are great if you’re a mechanical guy that wants to go fast, because everything fits everything in GM world. But I was a professional mechanic. Being cheap, GM didn’t deburr (remove sharp edges on) their stampings. Consequently, every time I stuck my hands in a GM engine well to do a tune-up or replace a master cylinder, I pulled out two wads of hamburger. The biggest lacerations I ever got were from GM’s.

I quickly learned to hate them.

Chrysler products never fit together right, as though they were designed by committee. Frustrating to work on they were back then. That observation wasn’t far from the truth. Opposed to the GM world of interchangeability, Ford platforms were well designed around the platform, but the platforms didn’t much talk to each other. That’s why the weekend hot-rodders mostly played with GM products. Chrysler and Ford products could make really big power, but it cost $$$ to reveal it and a lot of thought on how to get there.

Which one was better? For me, it was Fords. Unlike GM’s, Ford’s carburetors rebuilt easily, tune-ups didn’t require breaking out the first-aid kit and unlike Chrysler, they fit together in a logical order.

My point of view was from the aspect of maintenance, not hot rodding. Fords were just easier to maintain.

Years later, I became acquainted with espresso machines. In the ACM years from the mid 90’s to the mid-teens of the 21st century, I dove into almost every major brand out there. Harkening back to my automotive experience, I applied many of the same criteria for observations. In those early years when asked what I thought was the best espresso machine I would answer,” Astoria.” Built by CMA in Susegana, Italy, the Astoria model I was most familiar with then was called the Argenta.

These machines were very straight forward, easy to disassemble, logically thought out, perfect from my viewpoint of maintainability. I’m rebuilding a 20-year-old Argenta as I write this blog.

But there are drawbacks to this perfect espresso machine. They have to do with how the group head is heated.

So, I’ll try not to get too technical with this. The group head is where the handle full of espresso coffee is put into the espresso machine. The group head needs to be kept hot otherwise the first bit of water put through the coffee would be cold—below brewing temperature anyway. Since we’re only talking about 1 ounce of water, any cold water would greatly affect the quality of the espresso. The water through group must be kept hot to extract (brew) properly.

How is that accomplished, you ask. There are 3 ways I’m familiar with.

The first way is direct heat by conduction through metal. The group is bolted directly to the boiler and is heated via contact with the boiler’s scalding hot water. The group head is fed with one hot water line. This is the method used in the Argenta.

The second way is a convection system called “thermal syphoning.” In an oversimplification, the group head uses two lines, an upper one for hot feed water and the lower one for cooler return water. The group head acts like a radiator, cooling off water that sinks back and draws in fresh hot water. Most espresso machines now, including Astoria, use this method or variations of it to maintain group temperature.

The third method uses a separate boiler on the group with its own heating element. These systems often allow the user to individually control the group temperatures. More hardware and digitals are employed in this method making the machines pricey.

The Argenta’s drawbacks. First, it takes time for heat to migrate from the boiler to the group. And that heat can be locally depleted. Second, water standing in the feed pipe is not hot. There may be a couple ounces of water that is not at optimal temperature sitting in the system. A double shot of espresso is a couple of ounces. Hence, the operator should run hot water through the system to heat everything up.

What all this amounts to is instability in the water temperature from the group. Mind you, this instability only shows up through infrequent use. It’s not much of an issue in a busy shop that’s pumping out espresso drinks with milk and sugar and flavors. It becomes an issue when the groups aren’t warmed up.

So, my beloved Argenta (the first espresso machine I really learned to work on and the first espresso machine model that I built literally hundreds of, and the first espresso machine I fell in love with) is not the best espresso machine.

So, which is the best? Like a car, it depends on what you want your machine to do, and how much money you want to spend. If you want everything and have unlimited funds, both Italy and the US offer some very stylish, high-end machines. As the price comes down, manufacturers tend to spend money either on how the machine works or how the machine looks. As the price gets lower, style loses to function until a point is reached that even function is sacrificed.

I suppose the first and probably the most important aspect is price. If it’s a home machine, get what you can afford. More money generally gets you more functionality and more longevity. If for a business, consider whether this machine will be showcased in the front of the house and style is the important factor. Or will it be more out of sight in the back of the house where functionality and longevity are the greater consideration.

When shopping for an espresso machine, look around. Ask questions. Education is the best tool for making that decision. When you’re ready, buy from a reputable dealer. Be leery of on-line purchases. I’ve worked on hundreds of machines from E-Bay. Not all of them went well. You learn what to look for, what to stay away from, which are great buys, and which aren’t. If you do find your perfect machine and decide to purchase on-line, know somebody who can get you out of a jam. Dealing with a damaged or frozen espresso machine can be a very expensive lesson to learn and one that can be easy enough to avoid.

I know.

–

Chris Stripling is the Facility Engineer for New Mexico Piñon Coffee and Lead Technician for Albuquerque Coffee Equipment.